The Spaces Between Belonging

- Charlene Holkenbrink-Monk

- Jun 22, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Oct 23, 2025

We had been in our new flat for a week when I walked into the kitchen of our new home for the next four months, looked at the pouches of ramen I brought from the United States to curb potential homesickness, and scrunched my nose.

We only had a few left, and the food I had brought from our last accommodations was getting old; we could only handle pan-cooked*, frozen pizza for so long. Aside from visiting a small chuchería chain, named Tejeringo's, we hadn't ventured out much in our barrio.

Tejeringo's had quickly become a favorite and I enjoyed the various types of coffee I could order. This is where I learned of the café bombón, which is now my new favorite drink. But, by this point, we were ready to try something new and needed something savory.

So, at around 20:02, hunger hitting, I turned and saw the wonderful groceries our landlord had bought for us in the week prior: liters of milk, plenty of muffins, a bag of apples, chips, bread, and olive oil. They helped with snacking, but with our limited options of ingredients, I proposed to my children that we visit the restaurant next door, Grupo Kaiser. On the outside, as one walks by, they are greeted by the sign, "Kaiser. American Food." I knew that Kaiser opened at 20:00, so I proposed to my children, "How about we try the place next door?"

As we walked in, we were greeted with decor one would expect to find in various establishments in the United States. Endless signs about Route 66, motorcycles, cars, and more adorned the walls. Other signs showcased cars, ice cream, zombies, beer, a list of "man cave" rules, Rosie the Riveter flexes, and more. Much like what is seen in the photo on the left, this was found throughout the entire restaurant, further supported by the retro-style yellow booths. While the restaurant retained its American-style decor, the culture and environment were distinctly different from the moment we stepped in, but we would learn over time how true this was.

A very nice man greeted us and motioned to a table, then handed us a menu. I chuckled as I saw the names of salads, a list of cars, and then even more so when I noticed their burgers, all named for various baseball teams in the United States, with the San Diego Padres and the Los Angeles Dodgers standing out to me. Sitting with the multiple options, I asked the server, whom I will refer to as U to maintain his identity, if we could order a pizza with only pepperoni, as they had some elaborate pizza options. He referred with a very friendly, "Claro." At that moment, we had no idea that this place would become integral to feeling like home, but it did.

However, this post is not intended to highlight this fantastic restaurant with equally as wonderful humans next door to our flat in Spain, but rather to talk about the spaces between belonging, a space I have been far too familiar with, and how the Fulbright helped me, for the first time, feel like I was no longer in that liminal space, but rather I felt like I had found a place that was home. For much of my life, I never felt like I had a home. Yes, I had a home that my dad worked hard to keep over our heads. Yes, I grew up in San Diego. When I moved to Los Angeles, I initially hated it, but by the end, I had made some fantastic friends. There were places where I felt like I almost belonged, but I still felt like something was missing.

Whether it was in a school program, where I watched people become best friends and develop lifelong friendships, meanwhile I hoped I'd receive a response to a text asking to spend time together, or I'd see colleagues and friends have amazing mentorship, while I wondered what was wrong with me and why I didn't get the same collaboration. I'd watch sitcoms highlighting friend groups that had children grow together, or see walking or brunch groups posted on social media, curious why I wasn't invited, or even navigating spaces where I felt uncomfortable, frustrated, or maybe even bored with the nature of the environment, I consistently, throughout my life, felt sad and out of place. The reality is that I was able to force myself to fit in, but I never truly belonged.

That is, until I moved to Spain. And for the first time, I didn't feel I needed individual people in the ways that I thought made me feel so disconnected before, but rather, this place wrapped me in its metaphorical arms and embraced me in a way I hadn't felt.

I will not pretend that the first month was hard. In fact, I remember writing in my blog the fear and trepidation I was feeling in my post A Good Night's Sleep. I hadn't read it since I wrote it until I started crafting this post, and realizing how far I have come is endearing, uplifting, and encouraging. But it's also heartbreaking in many ways, and I'll explain.

Those hours that I sat with grief, fear, anguish, and worry were evident in that blog post, in my feelings, and in my heart. I was terrified. I reached out to loved ones, colleagues, friends, and mentors and was met with mixed responses; some excitedly responded with, "You're doing great! Keep going," others gave a variation of, "Maybe this isn't a good fit for who you are," or, "I was really surprised you were going to do this afterall," and, "Just stay focused and you'll be okay." It felt dismissive in many ways, encouraging in some, but I absolutely felt alone. One night, I stared at my children, worried that I would fail them, that I had just dragged them across the globe only for me to fall on my face in front of them, facing some precarious living situation. I cried. A lot.

And then things started falling into place. It felt serendipitous, perhaps even synchronistic. I started seeing what may or may not have been "signs," such as the Bad Wolf, a reference to Doctor Who, spray-painted on the building across the way from our flat (and I am a huge Doctor Who fan). We moved into our flat, and the world finally felt just better. We became regulars, waving and smiling kindly as we walked by the family who owned the bazaar next door. When they had a new small delivery of Snickers ice cream, as we walked in, they would ask, "¿Quieres helado de Snickers?" and we'd respond with a confident, "¡Vale, vale!" We started becoming familiar faces in our neighborhood. It felt nice.

We had a go-to churrería, where they served our beloved tejeringos. We stopped by the coffee shop down the street, a store that allowed you to be surrounded by books while sipping your batido de Oreo or enjoying our tarta de zanahoria. We bought a bus pass card, and would reload it at the tobacco shop; we had a particular one since there was one within a 5-minute walking distance in almost every direction. We would take the 14 bus, which was our bus, and knew at what times the drivers changed. Of course, we took other bus lines depending on where we needed to go, but this one took us to the center, which is where we ventured into different parts of Andalucía. We visited the cat café, and as we began to remember all the cats' names, they started recognizing us.

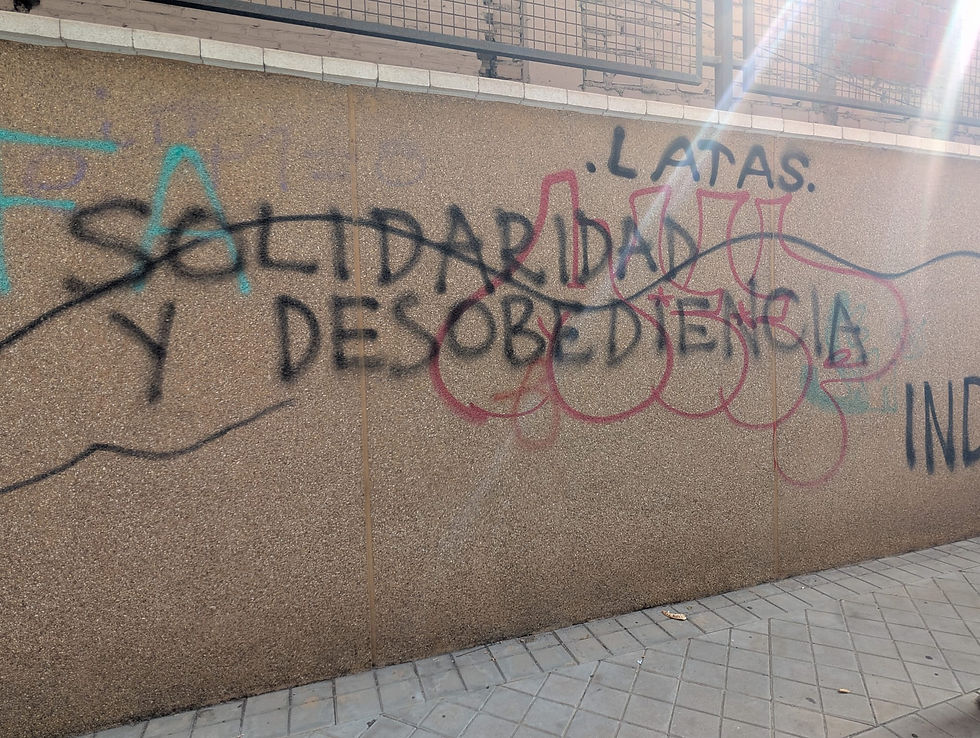

I collected significant data for my research project, which helped put me on a slightly

different, yet exciting, research path. I began to see the ways that street art and graffiti can serve as a critical analysis and public pedagogy, particularly in Málaga and throughout Southern Spain, due to the heavy political art present in the region. I began refining my writing, recognizing what I am truly passionate about: writing, creativity, storytelling, and

community connections. I stopped exerting so much energy into academic tenure-track applications that brought me down into despair, consistent reminders that this is a rat race I never wanted to be a part of. I stopped focusing so much on what I need to do, all of the things I "should" do, and started researching groups and spaces in San Diego where I could begin focusing on my fiction stories. I started feeling like a full human, a concept that I teach heavily in my classes, encourage my students to do, but have rarely been able to express or model in my own life. I had two book chapters accepted with incredibly positive feedback, telling me that my work was a "rich, lyrical, and powerful piece" and "Your piece is a beautifully crafted, deeply personal, and intellectually rich exploration... without losing the emotional and sensory depth of the storytelling..." Meanwhile, through all of this, I received excellent student evaluations on asynchronous courses, highlighting my ability to not just teach, but still connect with my students despite the "disconnected" nature of online, distance education.

I was not merely trying to fit in; I belonged. And for the first time in my life, I felt incredible, in my element, and there was a wholeness in my soul that I had felt minimally in my life.

I was thriving, when often in much of my life, I have merely known what it is like to survive.

The reason I find it both endearing and heartbreaking is that, at some point, I realized this is all temporary. The plan was to never stay in Spain, and in fact, I had only chosen a four-month grant due to the hesitation and concern that we had our lives in this country, so at least four months would be manageable. I had no idea the possibilities this would open up for me. Sure, I knew that this was an incredible opportunity that not everyone has the opportunity to pursue. Yes, I understood that this would be an excellent line on my CV, potentially contributing to more responses in the academic world (sidenote: it really hasn't.) But the transformation was so much more than just a professional endeavor; this was life-changing.

I managed to pack parts of my and my kids' lives up into three suitcases and three backpacks, travel around the globe, and live in another country. I then mapped out amazing trips within Spain, traveling to Granada, Ronda, Córdoba, Seville, Setenil, Benalmádena, and Madrid. I planned small travels through Europe on our way out, visiting Zurich and Dublin. In those spaces, I learned how to take public transportation in foreign countries without hesitation, something that I struggled to do in the United States due to severe anxiety. I became comfortable with hailing taxis, making small talk, something I struggle to do anywhere else, and sharing laughter with people I would never see again.

I explored medieval architecture in Switzerland, appreciating the country's rich history and

its trams, which are quick to load yet easy to use. And I fell madly, deeply in love with Dublin and Ireland as a whole, aligning with its love of storytelling, fantastical mythology, kindness, and its support of its community through small acts such as free Wi-Fi and charging ports on their double decker buses, as well as its history of fighting against oppression and its recognition of colonialism. I shared conversations with a woman who noted she learned about Native American history in grade school and noticed the similarities to the history of the North of Ireland and its relationship with Britain, days after having an amazing conversation with our taxi driver on the history and politics of the United States.

The experiences I had are unforgettable. I used to lament about the ways that I missed out in my twenties on living abroad, traveling the world, and how I kicked myself for not trying harder to do that when I was younger. I was too busy juggling survival, I had to work more than full-time, and realistically, I didn't think it was within my reach. The last part was the most important: I didn't know it was within my reach. But perhaps things worked out as they were supposed to, because I wouldn't have had these experiences if it weren't for my PhD, at least in the capacity that I have experienced them. If it weren't for the PhD, I wouldn't have started traveling for conferences, networking, or seen the possibilities. If it weren't for the PhD, I wouldn't have met others who had experienced research or teaching grants, specifically the Fulbright, and I wouldn't have known how to apply. If it weren't for the PhD, I wouldn't have received a scholar award that encouraged me to conduct my research at my own pace.

And if it weren't for the PhD, then, I wouldn't have experienced the path I have so far, resulting in finally feeling that I belong, no longer existing in the spaces between, and having that experience with my children. These opportunities were not even in my dreams as a first-generation kid from a working-class background. So to give this experience to my children while I have them, as well as incredible and beyond those nonexistent childhood dreams, has been the most rewarding.

I will admit that I have been living in a weird liminal space as of late. I have been back in the United States for a little over a week and have witnessed tremendous upheaval and concern on a global level. There is a "weirdness" so to speak about being back, having to transition to different cultural values, such as the slowness in Spanish dining compared to the fast paced nature that is expected in U.S. restaurants, or the casualness that takes place when interacting with people who you don't even know that I had in Málaga compared to the false "politeness" that is expected when engaging in the U.S. Depression hit heavy in the middle of the week, and I'm struggling. But not because life is dull, but rather it was vivid and full of color, it was lively and awe-inspiring when I was in Spain. I will transition and learn to love and appreciate where I am, my community, and find ways to replicate feelings of connectedness and solidarity with each other.

The Fulbright is more than some prestigious award. The intention is to help foster cross-cultural connections, global cultural exchange, and professional contributions. It has absolutely fulfilled that in my life and I know that my interactions have impacted others as well, like sitting at a coffee shop and chatting about the importance of political knowledge and critical conversations, comparing struggles and obstacles in Spain and the United States, or having a deep conversation with our taxi driver who explained he had to use a Tesla when he was driving Uber, and the time it took to charge cut into his time without pay. The graffiti around housing and other community obstacles allowed me to see how people experience life similarly yet differently in different parts of the world, a concept I understood but had not been immersed in. And I have built connections and relationships with people in these spaces, regardless of whether they will remain for a lifetime or not.

This is the beauty of the Fulbright. The stories we tell and create, the moments we share, the shared anguish and pain we commiserate in, the laughter we express, the language development, the cultural norms we learn, and the feelings of connection, humanity, and belonging are essential. The Fulbright is under attack and has been for some time, and academics and professionals are worried about what this means for the state of the program. As a now alumna of the program, I am heartbroken to see the possibilities for what I've experienced dwindle. We may also face frustrations as to what to do next, but this is why we tell our stories and continue to stand in solidarity: so that opportunities that can foster cultural connections, bridging divides through education, can remain.

It seems daunting right now, but we cannot lose hope. Not just with the Fulbright, but with our fight for connectivity, solidarity, community, and the humanization of us all.

__________________________________________________________________________________

All photos are pictures I have captured during my travels. If you'd like to see more of my photographs, you can find them here: Gallery

Additionally, I'd love for you to consider subscribing. It's free, but it helps support the work I do, and you'll get updates as I write more: Writing

*While it is more of an outdated idea for all of Spain, it isn't uncommon to find places without ovens in Andalucía, which is where Malaga is located. We stayed in two different flats during our first two weeks and then viewed four more before I signed our lease; none of them had ovens. The place we signed did not, either. And an interesting cultural shift for sure!

Comments